Michel Siffre’s Cave Experiment

For most of us, time is a persistent companion—a tick of the clock, a sunrise, the steady change of seasons. Our lives orbit around its rhythms, its strictures, its relentless march forward. Rarely do we question its objectivity; time seems as absolute as the ground beneath our feet. But what if time is not a universal constant, but instead, a mental construct, woven by our brains to navigate the chaos of existence? In the early 1960s, French speleologist and scientist Michel Siffre embarked on a radical experiment to test just that. His journey deep below the Earth’s surface, into the silent darkness of a cave, would transform our understanding of time, biology, and the mind itself.

Descending into Darkness: The Experiment

In July 1962, Michel Siffre entered a cave near Nice, France, and committed to spending two months in total isolation from natural light, clocks, or any external cues about the passage of time. His only instruments were those necessary for survival and a telephone connection to the surface, through which he could report his awakenings and sleep cycles, but never receive information about actual time.

This was not just an exercise in loneliness or endurance; Siffre’s goal was to probe the mysteries of the human biological clock. He wanted to discover how, in the absence of the sun and social structure, the mind would reckon with time. Would his body invent its own rhythms? Would he lose track of days? Was time, perhaps, merely a product of collective agreement and routine?

The Perception of Time: A Vanishing Metronome

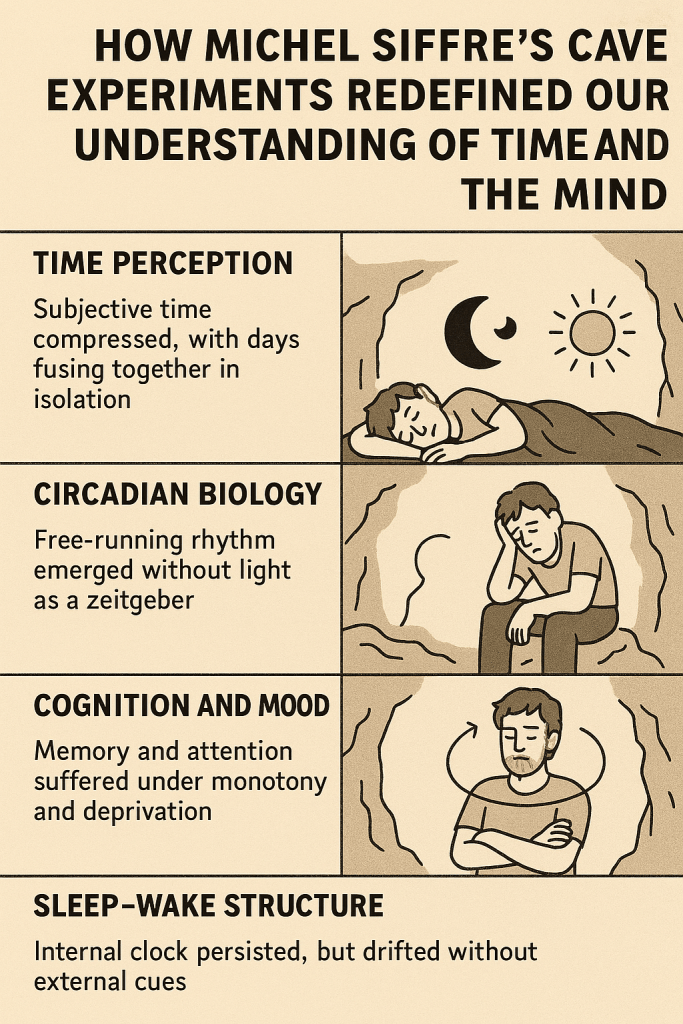

Siffre’s observations were haunting, almost dreamlike. Deprived of the sun’s cycles and any indication of the hour, he began to lose the ability to measure time subjectively. Days melted into one another. What felt like a week might have been two or three days; what felt like an hour could pass in minutes, or stretch into what seemed like eternity.

After emerging from the cave, Siffre recounted that when researchers told him the actual day and duration, he was staggered. He had believed he had spent 34 days in the cave, when in truth, 59 days had passed. His sense of time had dramatically slowed. In a later experiment, conducted in a cave in Texas for over six months, he routinely confused days and nights, sometimes staying awake for over 36 hours straight, and sleeping for up to 14 hours at a time.

This was not idiosyncratic: Siffre’s later experiments with other volunteers produced similar results. Isolated from external cues, the brain’s internal clock ran on a rhythm roughly—but not exactly—similar to the 24-hour cycle, often stretching to 25-30 hours. Without the anchor of sunrise and sunset, humans drifted, untethered.

The Internal Clock: Biology in Freefall

What was happening inside Siffre’s body and mind during these long stretches of isolation? The results were as remarkable as they were unsettling.

Our internal clocks, or circadian rhythms, are regulated by a small cluster of neurons in the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, which responds to light and darkness. These rhythms control everything from sleep and hunger to hormone release and body temperature. Siffre’s isolation revealed that, in the absence of light and time-keeping devices, the body’s rhythms become largely self-regulating, but not perfectly so. The “day” inside the cave lengthened, slipping away from the 24-hour standard.

Cognitively, Siffre and his fellow “time-nauts” reported lapses in memory, heightened anxiety, and difficulties in concentration. The mind, deprived of familiar structures, became foggy, sometimes hallucinatory. The sense of self, so often anchored in routine and social interaction, began to blur with the formlessness of time itself.

Time: A Construct, Not a Constant?

What do these findings suggest about the nature of time? Siffre’s cave adventures imply that time, as we know it, is not a rigid, universal metronome, but a psychological and social construct. The brain, in cooperation with environmental cues and cultural norms, “creates” time for us to make sense of experience, to coordinate with others, to survive.

Removed from those cues, the perception of time begins to dissolve. For Siffre, time became elastic—stretching, condensing, sometimes disappearing altogether. Our day-to-day sense of temporality is thus largely an illusion, a necessary fiction to organize experience.

This is both profound and unsettling. Day after day, we treat time as objective—a river we swim in, unyielding and universal. But Siffre’s experiment hints that time is a map our brains draw, not territory itself.

Does Slowed Perception of Time Slow Aging?

A tantalizing implication of Siffre’s findings is the question: if our perception of time slows, does our biological aging slow as well? The short answer is: not really, at least not in any meaningful sense.

Siffre’s slowed perception of time did not equate to slowed cellular aging. Biological processes remain tuned to internal cycles—cell division, DNA repair, metabolism—even if the mind becomes confused about the passage of hours and days. However, the disruption of regular circadian rhythms can have notable effects on health: increased stress hormones, sleep disorders, lowered immune response, and cognitive impairment.

In Siffre’s case, the lack of external cues and subsequent circadian drift may have temporarily altered some physiological processes, but it did not “pause” aging. Instead, prolonged isolation and loss of time structure can destabilize mental health, leading to anxiety, depression, and cognitive sluggishness. The body, it seems, cares about the cycles it’s used to, even if the mind is adrift.

The Mental Landscape of Timelessness

Perhaps the most profound lesson of Siffre’s caves is existential: our reality is stitched together by our perception of time. When that thread is broken—when days and nights, seconds and hours lose meaning—the mind wades into disorientation. Routine and external structure are not mere conveniences; they are fundamental to mental health and a coherent sense of self.

To live without time is to live in a fog, where memory, identity, and the very fabric of experience are frayed. Time’s illusion, then, is not trivial—it is necessary, a scaffolding for consciousness.

Echoes from the Deep

Michel Siffre’s experiments in darkness are more than curiosities of the scientific record. They are reminders of the mind’s creative power, and its vulnerability. Time, as we live it, is a dance between biology and imagination—a rhythm set by the brain, but conducted by the world around us.

While time may not be a complete illusion—our bodies still age, the world still changes—it is certainly not the absolute many believe it to be. Siffre’s journey into the caves is an invitation: to consider how much of what we take for granted is, in fact, a construct of mind. And to remember, as clocks tick and calendars turn, that the truest timekeeper may be neither the sun nor the watch, but the quiet, pulsing mind within.

Caveats and limitations

- Single‑subject beginnings: Much of the early evidence came from Siffre himself; generalizability is limited, though later replications and animal work broadly support free‑running rhythms and light’s primacy.

- Ecological validity: Caves are extreme settings; factors like stress, loneliness, and altered routines may amplify effects beyond everyday life.

- Variability across runs: Reports range from ~25‑hour drifts to episodic longer cycles; these are observations under unusual conditions, not a universal “new day length” for humans.

Practical takeaways

- Anchor your clock with light: Get bright morning light and dim evening light to keep your circadian rhythm aligned.

- Keep stable time cues: Consistent sleep/wake, regular meals, and social routines act as daily “reality checks” for biological and psychological time.

- Beware of cue deserts: Prolonged isolation or windowless environments can distort timing and cognition; add structure (timed tasks, scheduled breaks, light exposure) to protect performance.

- Design for rhythm, not against it: For demanding work (night shifts, travel, creative sprints), plan around your peaks and use light strategically rather than relying on willpower alone.

Leave a comment