In 1973, from a chair in California, an artist‑psychic named Ingo Swann claimed to project his mind across the solar system and “look around” Jupiter. In that altered state, he sketched faint rings around the planet—six years before NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft actually detected Jupiter’s tenuous ring system in 1979.

For believers, this remains one of the most tantalizing pieces of evidence that human consciousness can transcend space. For skeptics, it is a mix of coincidence, selective memory, and loose experimental design. The truth sits somewhere inside this tension.

This blog explores who Ingo Swann was, what “remote viewing” actually involved, how his famous Jupiter vision holds up under scrutiny, how scientists evaluated such claims, and whether abilities like this are considered humanly possible today.

Who Was Ingo Swann?

Ingo Douglass Swann (1933–2013) was an American psychic, artist, and author, best known as a pioneer of “remote viewing,” a term he helped coin and formalize. Born in Telluride, Colorado, Swann reported paranormal experiences from early childhood, including out‑of‑body episodes and seeing “auras” around people and objects.

After moving to New York and working as an artist, Swann became active in parapsychology circles. In the early 1970s, he participated in experiments at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) with physicists Harold Puthoff and Russell Targ. Those experiments, funded in part by U.S. intelligence agencies, aimed to test whether some people could acquire information about distant locations or targets without any conventional sensory input.

Swann was not just a subject; he also helped shape the methodology. He is commonly credited with developing “controlled remote viewing” (CRV) protocols—structured stages of impressions, sketches, and annotations designed to minimize guesswork and maximize whatever genuine “signal” might be present.

His work eventually fed into what became known as the Stargate Project, a long‑running, secret U.S. government program exploring psychic spying, which operated from the mid‑1970s until its termination in 1995.

What Is Remote Viewing?

Remote viewing (RV) refers to the alleged ability to perceive or describe a distant place, object, or event using only the mind, usually under controlled conditions. A typical protocol in the SRI era looked like this:

- A “tasker” selects a target—say, a military installation, a photograph, or a set of coordinates.

- The viewer is given minimal information (often just a number or coordinates).

- The viewer then reports impressions: shapes, textures, temperatures, emotions, sketches, and sometimes detailed narratives.

- Independent judges compare the session data with possible targets to see if there is statistically significant matching above chance.

Swann’s contribution was to emphasize structure: stages of perception (from vague sensory impressions to more conceptual descriptions) and a discipline about separating “signal” from “analytical overlay” (the mind’s tendency to interpret and fill gaps).

At least on paper, this looked like an attempt to bring scientific rigor to a very speculative phenomenon. The Cold War atmosphere and intelligence agencies’ fear of “falling behind” Soviet psychic research helped ensure funding.

The Jupiter Experiment: A Psychic Probe of a Giant

Swann’s most famous session took place on April 27, 1973, at SRI. Rather than a terrestrial location, Swann proposed something far more audacious: a “psychic probe” of Jupiter, years before any spacecraft had flown past the planet.

Setup and Procedure

According to accounts based on declassified CIA documents and SRI reports, the experiment proceeded roughly as follows:

- Swann sat in a room at SRI with Puthoff and Targ acting as monitors.

- The target—Jupiter—was not disclosed explicitly at first; Swann was asked to extend his perception to a specified location in space.

- After a brief quiet period, Swann began describing what he “saw,” with notes and sketches recorded in real time.

- A formal report, “Swann’s Remote Viewing Probe of Jupiter,” was later prepared, and portions of it appear in CIA archives under an experimental psychic probe of the planet.

What Swann Claimed to See

In multiple retellings and in reconstructions from the raw data, Swann made several key claims about Jupiter’s environment:

- Atmosphere and composition

He described a “poisonous” atmosphere containing hydrogen, helium, ammonia, methane, and possibly heavier isotopes like deuterium—all broadly consistent with what modern planetary science confirms about Jupiter’s gaseous envelope. - Weather and dynamics

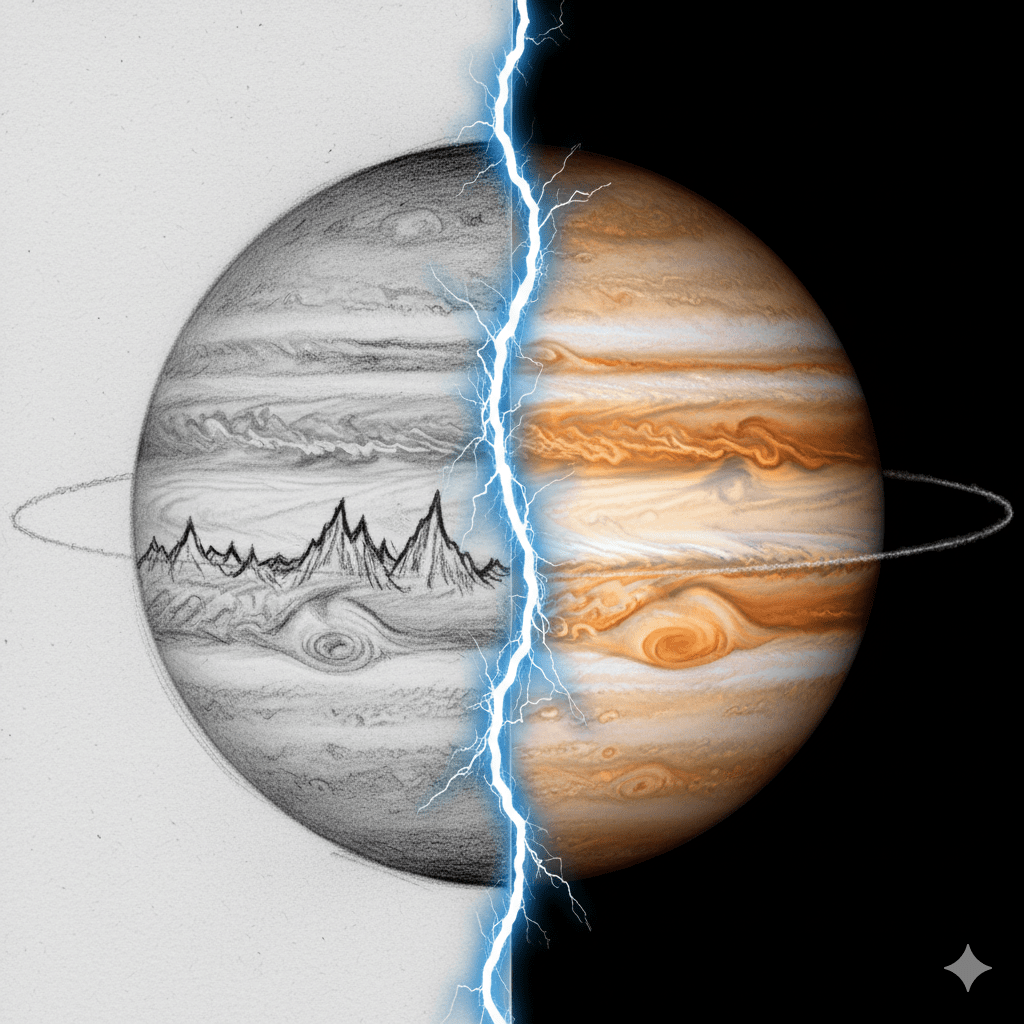

He spoke of “gigantic storms and wind” that blow clouds around, and a heavily banded, turbulent atmosphere—features that match the well‑known belts, zones, and long‑lasting storms such as the Great Red Spot. - Crystals and “rings”

Crucially for his legend, Swann mentioned “crystals” high in the atmosphere, glittering and forming bands he likened to “rings,” comparing them to Saturn’s rings but “very close” to the planet rather than far out. In some summaries, he flatly states there is a “ring” or flattened ring structure. - A moon with volcanic activity

Swann also reported impressions of volcanic activity, orange‑yellow colors, and surface turbulence on a nearby moon—often interpreted as a rough description of Io, whose intense volcanism was dramatically confirmed by Voyager in 1979. - Solid features or “mountains”

He referred at times to something like “mountains” or very tall structures protruding through atmospheric layers, which is harder to reconcile with Jupiter’s status as a gas giant without a solid surface in the terrestrial sense.

Later Confirmation

At the time of Swann’s session, Jupiter had been studied extensively by telescopes and spectroscopy, but no spacecraft had yet visited. The Pioneer 10 and 11 flybys were in 1973–1974, and the discovery of Jupiter’s rings did not come until Voyager 1’s 1979 pass.

Voyager eventually confirmed:

- Jupiter has a faint ring system composed mainly of dust.

- The planet’s atmosphere is largely hydrogen and helium with ammonia and other compounds, plus massive storms.

- Io is intensely volcanic, with active eruptions and sulfurous plumes.

These later findings allowed proponents to retroactively highlight Swann’s references to rings, crystals, and volcanism as striking “hits.”

How Impressive Are the “Hits,” Really?

To assess Swann’s Jupiter vision critically, two questions are crucial:

- What exactly did he say, in the original raw data?

- What was already known or reasonably guessable in 1973?

Ambiguity and Retelling

The surviving raw transcripts from the SRI session are relatively short—on the order of a few pages—while later write‑ups and Swann’s own retrospectives run to hundreds of pages, mixing original statements with subsequent scientific data. Over time, accounts tend to:

- Emphasize accurate‑sounding statements (“very thin rings,” “volcanic moon”).

- Downplay or omit misses or unclear descriptions (e.g., “mountains” on Jupiter).

- Translate ambiguous wording (“bands of crystals… maybe like rings”) into more definitive claims (“he predicted Jupiter’s rings”).

This process of retrospective sharpening is common in paranormal case histories and makes objective assessment difficult.

What Was Already Known?

By 1973, planetary astronomers already knew a fair amount about Jupiter:

- Spectroscopy had revealed hydrogen and helium dominance with ammonia and other compounds.

- Telescopic observations had documented banded clouds and long‑lived storms, including the Great Red Spot, for more than a century.

- Fast rotation, strong magnetic fields, and intense radiation belts were recognized features.

Given this, a reasonably informed guesser—or someone exposed indirectly to popular science content—might plausibly describe storms, banded clouds, and a hydrogen‑helium atmosphere without paranormal input.

The more remarkable elements are:

- Rings: prior to Voyager, the scientific consensus was that Jupiter did not have rings, though Saturn’s rings suggested giant planets could host ring systems in principle.

- Io’s volcanism: before Voyager, Io was not known to be volcanic; its status as an active world was a genuine surprise.

Swann’s references to “rings” and “volcanic” moon activity, therefore, do stand out as interesting correspondences.

Coincidence vs Signal

From a statistical perspective, the key issue is not whether there are some matches, but how many specific, non‑obvious details were correctly identified relative to:

- The total number of statements (including wrong or vague ones).

- The prior probability of guessing such features.

- Independent replication by other viewers under similarly blind conditions.

Swann’s Jupiter case is striking anecdote, but it is still a single case, heavily filtered through decades of retelling. There is no broad, replicable body of planetary remote viewing data with similarly specific and surprising predictions later confirmed by spacecraft.

Scientific Evaluation: From SRI to Stargate

Swann’s success at SRI fed directly into greater interest (and funding) from U.S. intelligence agencies. This culminated in the Stargate Project, a multi‑decade program exploring remote viewing for military and intelligence purposes.

Mixed Internal Assessments

Within the program:

- Some early lab experiments at SRI and later sites reported statistically significant deviations from chance, suggesting that “something” beyond random guessing might be occurring.

- Ever‑optimistic parapsychologists such as statistician Jessica Utts later argued that overall data across psi research, including remote viewing, show small but robust effects under controlled conditions.

However, independent critiques were often scathing:

- Psychologist Ray Hyman, a leading skeptic, reviewed the same body of data and found that methodological flaws—sensory leakage, improper randomization, inadequate blinding, and flexible statistical analysis—could explain the reported effects.

- A 1990s review commissioned by the CIA and conducted by the American Institutes for Research (AIR) concluded that remote viewing had never produced actionable intelligence. The information was typically vague, ambiguous, and not reliably better than educated guessing.

The final CIA/AIR review stated that even if a small statistical effect existed in some lab studies, it had no clear operational utility. On that basis, the program was terminated in 1995.

Brain Activity Studies

There were also attempts to look at the brain. In 2001, neuropsychologist Michael Persinger published a study examining Swann’s brain activity during remote viewing tasks. He reported specific patterns in occipital, temporal, and frontal regions that appeared to correlate with stimuli, and concluded there was “significant congruence” between brain signals and task demands.

However, such findings show at most that Swann’s brain was doing something distinctive while he believed he was remote viewing. They do not demonstrate that information was being acquired paranormally, as similar patterns could arise from imagination, visualization, or focused attention.

Overall Scientific Reception

The broader scientific community has not accepted remote viewing as a real, demonstrable ability. Major reasons include:

- Lack of robust replication: Positive results have tended not to replicate when independent groups apply stricter controls.

- Methodological issues: Many early studies lacked adequate blinding, had small sample sizes, or allowed subtle cues to leak information.

- Vague outputs: Remote viewing data are often general enough to invite generous scoring, especially when judges know the correct targets.

- Theoretical implausibility: There is no widely accepted physical theory explaining how information about distant, shielded targets could be transferred without energy or signals detectable by current science.

As one summary of remote viewing research notes, mainstream scientists reject it largely due to “the absence of an evidence base, the lack of a theory which would explain remote viewing, and the lack of experimental techniques which can provide reliably positive results.”

Are Such Abilities Humanly Possible?

This is ultimately a question about both evidence and theory.

From the Evidence Side

Across more than a century of psychical research and decades of government‑funded projects, some patterns are consistent:

- Anecdotes are compelling, but isolated. Cases like Swann’s Jupiter session are narratively powerful but rest on small numbers, retrospective interpretation, and limited documentation.

- Laboratory effects, when reported, are small and fragile. Meta‑analyses sometimes find slight deviations from chance in psi experiments, but these are modest, often driven by a few studies, and highly sensitive to assumptions about methodology and publication bias.

- High‑stakes applications have failed. Stargate and similar programs around the world never produced a track record of solid, actionable successes that would convince skeptical analysts or justify continued funding.

On balance, the empirical case for reliable, high‑resolution, Swann‑style remote viewing is weak according to mainstream scientific standards.

From the Theory Side

For abilities like remote viewing to be “humanly possible” in the literal sense—information transfer across large distances without conventional signals—some deep issues arise:

- Causality and information: Current physics, including relativity and quantum theory, severely constrains faster‑than‑light or nonlocal information transfer in ways that prevent usable signaling.

- Energy and detection: If information about distant targets is being picked up, some form of interaction or field would presumably be involved, yet no such field has been robustly detected.

- Brain as receiver? Speculations that the brain might act like a quantum receiver or antenna for remote information remain unsupported by detailed models or testable predictions.

This does not prove such phenomena are impossible in principle—science can be surprised—but it sets a very high bar. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and that evidence has not yet materialized.

So What Do We Make of Ingo Swann?

Ingo Swann occupies a fascinating place at the border of science, myth, and Cold War history:

- As a cultural figure, he helped crystallize the idea of the “psychic spy” and inspired countless books, films, and spiritual movements.

- As a methodologist, he imposed structure and discipline on what might otherwise have remained pure free‑form clairvoyance, influencing how many later practitioners approach intuition and visualization.

- As a scientific case, his most famous successes, like Jupiter’s rings, are intriguing but not conclusive. They highlight the difficulty of separating signal from noise, hits from misses, and genuine foresight from pattern‑seeking in hindsight.

From a strictly scientific standpoint, the consensus today is that remote viewing as Swann envisioned it has not been demonstrated in a way that satisfies robust experimental scrutiny. Neither Ingo Swann nor the government programs that followed him produced evidence strong enough for mainstream science to accept remote viewing as a real, operational human ability.

Yet the story continues to resonate because it speaks to a deep human intuition: that mind might be more than neural machinery; that consciousness could have untapped dimensions. Whether one treats Swann as a visionary explorer of those possibilities, as a gifted storyteller, or as a bit of both, his legacy forces a sharpened question:

How far can the human mind really reach—and how would we know?

For now, the responsible answer is: such dramatic remote‑viewing abilities remain unproven and unlikely under current scientific understanding. But the curiosity that drove Swann to “look” at Jupiter from a lab in California—our drive to test the boundaries of perception and reality—that is unquestionably, and enduringly, human.

Leave a comment