1. Why Talk About Paley Today?

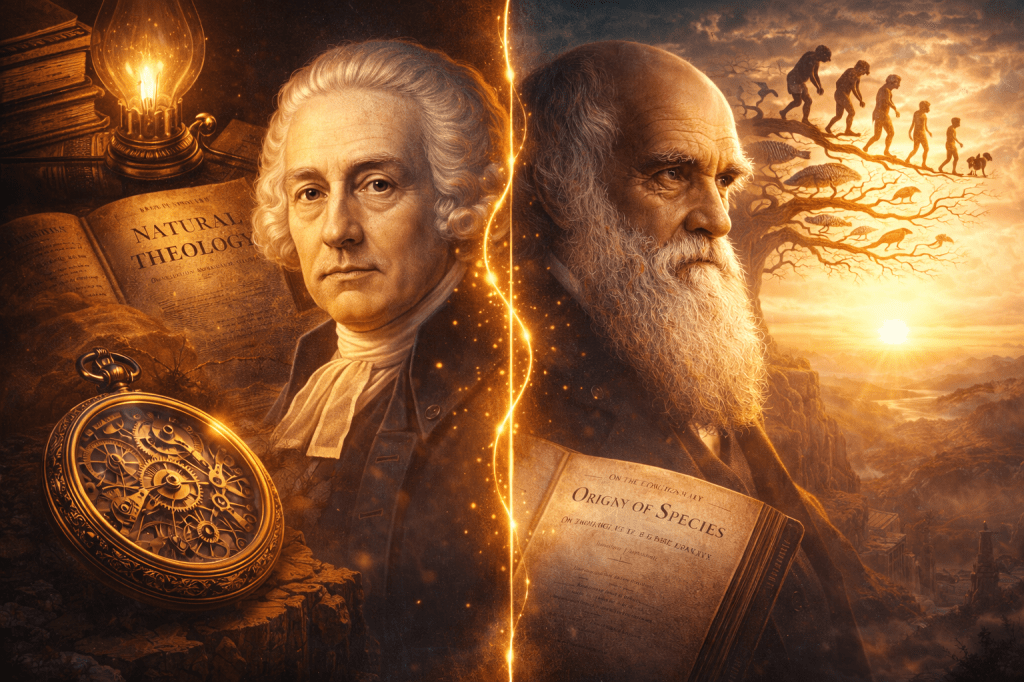

In 1802, English clergyman William Paley published Natural Theology, a book that tried to “read” God’s existence and character from nature itself. At its heart is the famous “watchmaker analogy,” which has influenced theology, philosophy, and even modern Intelligent Design (ID) debates.

A century and a half later, Charles Darwin would say that Paley’s argument, which once seemed “so conclusive,” failed once the law of natural selection was discovered. Understanding that shift reveals not only a clash between two ideas, but an evolution in how humans explain the world.

2. Paley’s Project: God Through Nature

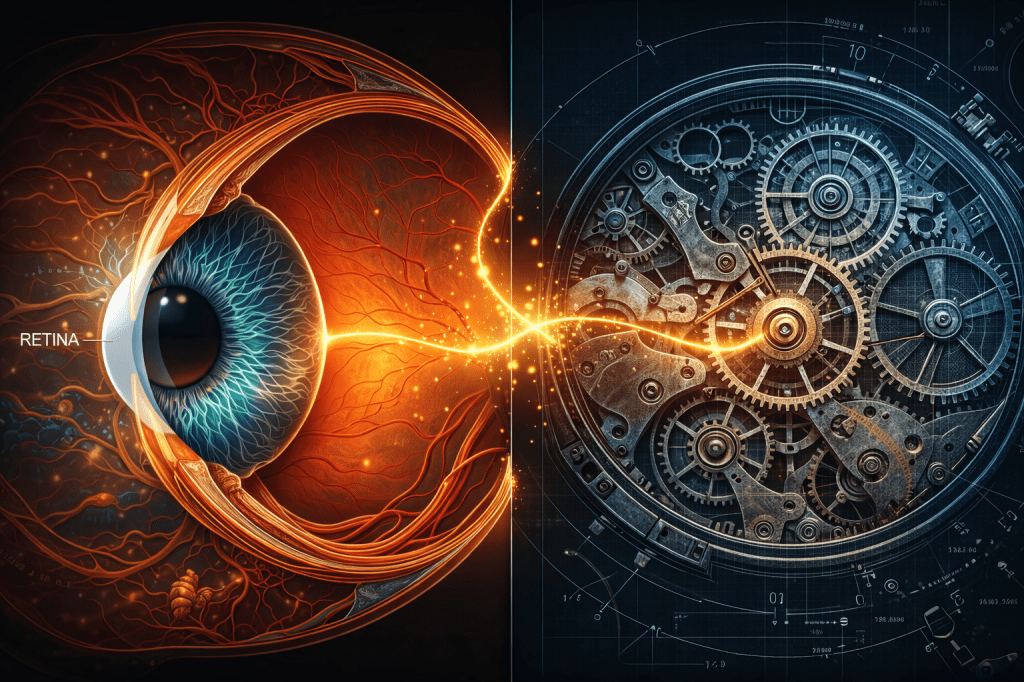

Paley lived in an age of machines—clocks, pumps, instruments. People increasingly thought of bodies as mechanisms: bones as levers, the heart as a pump, the eye as an optical system.

In Natural Theology, Paley argued that by studying such “mechanisms” in nature, one could infer a divine Engineer. He did not rely on scripture alone, but on reason and observation. In his view, the complexity, order, and usefulness we see in living things are not brute facts; they are evidence of a wise and benevolent Creator.

3. The Watchmaker Analogy Explained

Paley’s famous thought experiment is simple and vivid.

You are walking across a field and stub your toe on a stone. You might shrug and say it has just “always been there.” Now imagine that instead you find a watch. You open it and see springs and gears arranged in a precise way to tell time. Even if you had never seen a watch before, you would not say it had just always been there. You would infer that it had a maker.

Paley then draws the parallel:

- A watch, with its complex, purposeful arrangement of parts, implies a watchmaker.

- The natural world—eyes, wings, organs—shows even more complex, purposeful arrangements.

- Therefore, the natural world implies a cosmic “watchmaker”: God.

Formally, the argument runs like this:

- Watches are complex systems whose parts work together for a purpose.

- Such systems are the product of intelligent design.

- Living things also are complex systems whose parts work together for purposes (seeing, flying, digesting).

- Therefore, living things are products of intelligent design.

Paley adds that:

- Even a malfunctioning watch is still clearly designed.

- Even a single instance of such complexity is enough to infer design.

- The many independent cases of apparent design in nature form a powerful cumulative case.

4. Strengths of Paley’s Argument

Paley’s argument is not just clever wordplay; it has real strengths, especially seen from his time.

First, it matches everyday intuition. Whenever we encounter something highly complex and functional—a smartphone, a computer, an aircraft—we naturally assume a designer. Paley simply says: nature looks like that, only more so.

Second, he grounds his reasoning in empirical detail: anatomical examples, the structure of the eye, the hinge-like action of joints, the apparent fine-tuning of organs to their roles. This made his case feel like it was built on real science, not abstractions.

Third, his argument is cumulative. Each new example of contrivance is another strand in the rope. Even if one example is mistaken, the overall picture seems to remain.

Finally, Paley weaves his design argument into a larger theological and ethical vision. For him, the design and general “happiness” of creation point not just to a powerful cause, but to a wise and good God, aligning natural theology with Christian morality.

5. Early Cracks: Philosophical Objections

Even before Darwin, philosophers had raised serious doubts about design arguments. David Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (though Paley likely knew them only indirectly) are especially important.

Hume questions whether the analogy between a watch and the universe really holds. We know watches are designed because we have direct experience of watchmakers. We have no such experience of “world-makers.” The universe might be more like an organism that grows than a machine that is assembled.

He also notes that, even if design were granted, the evidence would not clearly point to a single, all-powerful, all-good deity. Perhaps many gods collaborated. Perhaps the designer is limited or morally indifferent, given all the suffering and disorder we see.

The problem of evil also bites: if good design shows God’s goodness, what do disease, natural disasters, and “botched” biological features show? Paley tries to answer, but the challenge remains serious.

6. Darwin’s Breakthrough: Natural Selection

The real turning point comes with Charles Darwin. As a student at Cambridge, Darwin admired Paley. He felt convinced by Natural Theology and absorbed Paley’s habit of explaining organs in terms of their function.

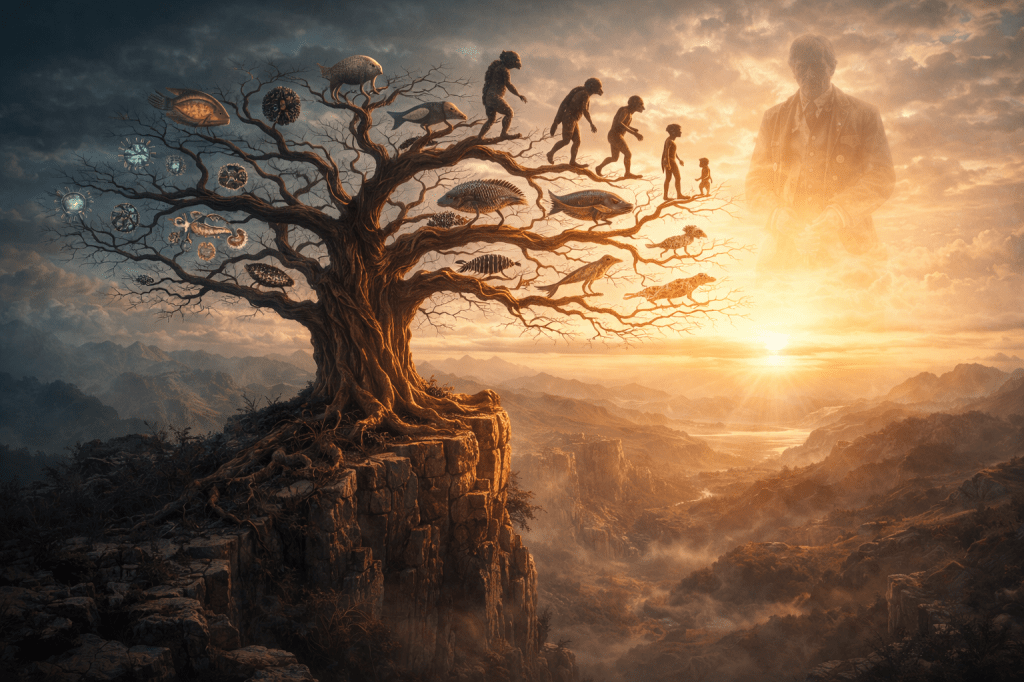

Darwin kept Paley’s question—how do we explain the fit between organisms and their environments?—but changed the answer. Instead of direct divine design, he proposed evolution by natural selection:

- Organisms vary.

- Some variations confer survival or reproductive advantages.

- These variants are more likely to be passed on.

- Over long periods, this process can build highly complex, well-fitted adaptations.

Crucially, this process is blind. There is no foresight, no planning; yet the outcome can look as if it were designed.

Darwin later wrote that Paley’s argument from design “fails, now that the law of natural selection has been discovered.” Once a powerful natural mechanism can explain the appearance of design, the inference to a divine watchmaker is no longer the only or best explanation.

7. Paley vs Darwin: Two Ways to Explain “Design”

Seen side by side, Paley and Darwin offer rival accounts of the same facts.

- Source of order: Paley: intentional mind; Darwin: cumulative selection of variations.

- Bad design and suffering: Paley struggles to harmonize them with a good God; Darwin expects imperfections, vestigial organs, and suffering as natural byproducts of evolution.

- Explanatory reach: Paley focuses on particular organs. Darwin’s theory extends to fossils, biogeography, and deep anatomical similarities via common descent.

Darwin’s approach does not prove there is no God. It does, however, show that the appearance of design in biology can be accounted for without directly invoking a Designer. This undercuts Paley’s argument as a necessary inference from biology to God.

8. Paley and Intelligent Design Today

The modern Intelligent Design movement is, in many ways, a revival of Paley’s style of reasoning. Instead of watches and eyes, ID proponents talk about:

- “Irreducible complexity” (systems that supposedly cannot function if any part is removed).

- “Specified complexity” (patterns they claim cannot arise by chance and natural law alone).

They argue that some biological structures cannot plausibly evolve step by step and therefore require an intelligent cause.

However, mainstream science sees ID as facing the same core problem Paley did, only more intensely:

- Evolutionary biology has steadily offered detailed, testable explanations for many systems once claimed to be “irreducibly complex.”

- ID often functions as “we can’t see how this evolved, therefore design,” which is an argument from ignorance rather than a positive research program.

Paley’s logic, repackaged, still struggles against the growing explanatory power of evolutionary theory.

9. What Remains of Paley’s Legacy?

As a direct scientific explanation of life’s complexity, Paley’s watchmaker analogy is no longer credible. Evolution by natural selection—and the broader modern synthesis with genetics—does that job far more effectively.

Yet Paley’s deeper intuition—that the universe’s order and intelligibility might point to mind—persists in other forms. Many contemporary theistic arguments focus less on specific organs and more on:

- The apparent fine-tuning of physical constants.

- The mathematical elegance of natural laws.

- The very existence of a law-governed cosmos.

In that sense, part of Paley’s project has migrated from biology to cosmology and fundamental physics.

Historically, Paley remains important as the clearest expression of pre-Darwin “design thinking” and as a major intellectual influence on Darwin himself. He shows how powerful an argument can seem in one scientific era—and how that power can erode when new theories arrive.

10. Conclusion: Between Watch and Wind

Paley’s watchmaker analogy endures because it dramatizes a basic human habit: when we see intricate structure and purpose, we instinctively look for a mind behind it.

Darwin did not erase that instinct, but he showed that, at least in biology, such structure can emerge from blind processes governed by natural law. The “watch” can, in effect, assemble itself over millions of years, without a watchmaker constantly at the bench.

Where one sees divine craftsmanship and where one sees the patient work of natural selection often reflects deeper commitments about God, meaning, and the nature of explanation. Paley and Darwin mark two poles of that conversation—a conversation that, despite scientific progress, continues wherever people look at the living world and ask what, if anything, it is trying to say.

Leave a comment